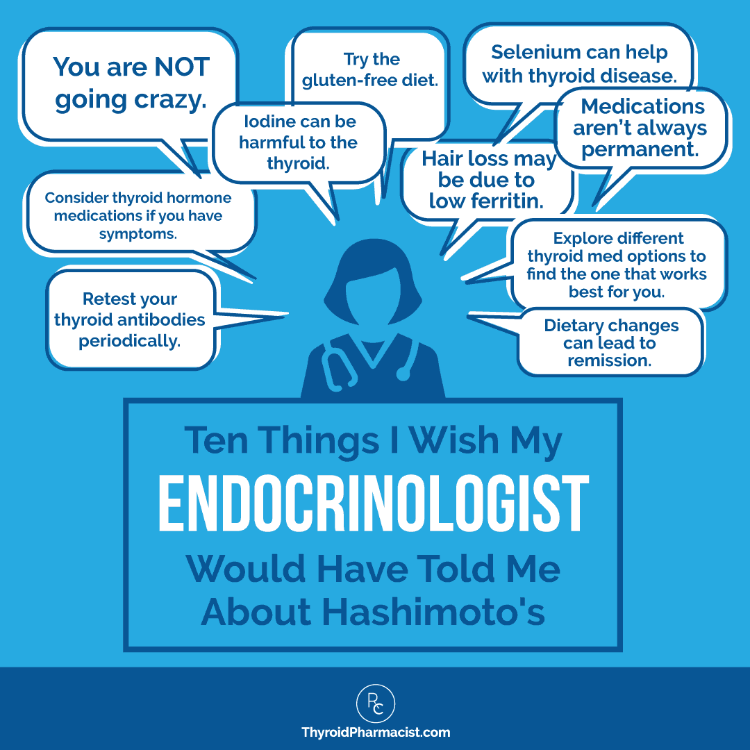

10 Things I Wish My Endocrinologist Would Have Told Me

October 1, 2020

Medically reviewed and written by Izabella Wentz, PharmD, FASCP on September 8, 2021

When I first started experiencing symptoms (before my Hashimoto’s diagnosis), and before I had started thinking that they could be related to my thyroid, I faced a lot of challenges in getting the adequate diagnosis and treatment for my condition.

I spent almost a decade undiagnosed because I only had my TSH levels tested. I had been told that my thyroid was normal, even though my TSH was 4.5 μIU/mL.

I continued experiencing a worsening of my symptoms (along with some new ones!). However, it wasn’t until my TSH levels had skyrocketed to 8 μIU/mL (back then, 0.4-4.0 μIU/mL was considered the “normal” TSH reference range), that my doctor referred me to an endocrine specialist.

I was eventually diagnosed with Hashimoto’s, but didn’t feel like I had a good understanding of what was really going on with my thyroid. I was trained as a pharmacist, and conventional medicine’s go-to for addressing thyroid conditions is primarily focused on prescribing thyroid medications. Endocrinologists are the designated medical experts for thyroid issues. However, most endocrinologists are not taught about the root causes behind the development of Hashimoto’s, or the lifestyle interventions that can help a person feel significantly better.

If you feel like you’re still trying to understand what is going on with your thyroid, or if you’re trying to get a deeper understanding of Hashimoto’s, I’d like to share with you a few things that would have been helpful to know at the beginning of my journey.

In this article, I’ll discuss:

- The different thyroid medication options available today

- How gluten and diet choices impact the thyroid

- Why iodine can exacerbate thyroid disease

- The connection between the thyroid and mental health

- Markers of thyroid dysfunction

1. Thyroid Medication Can Help with Symptoms — Even in Early Stages

If you are having symptoms of subclinical hypothyroidism — like fatigue, weight gain, sadness/apathy, hair loss, fertility challenges, cold intolerance, brain fog, and joint pain — it may be helpful to start thyroid hormones, if you haven’t yet been prescribed any.

Hashimoto’s has five progressive stages — subclinical hypothyroidism is the third stage. This is the stage when thyroid labs come back “normal” but the individual is experiencing symptoms such as weight gain, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic fatigue, and gastrointestinal disturbances, among others.

In a lot of cases, the “normal” lab results do not reflect what is actually happening within the body. For example, in the case of subclinical hypothyroidism, while T4 and T3 thyroid hormone levels may be within normal ranges, thyroid antibody levels may be elevated. Antibodies can be elevated for years prior to a proper diagnosis, and can contribute to the symptoms mentioned above.

However, studies have found that starting thyroid hormones can make us feel better and even slow down the progression of the condition. By helping the body produce optimal amounts of thyroid hormones, appropriate medication management can allow us to recover from the effects of hypothyroidism and will give us energy, vitality, and support to continue working on optimizing our health.

T4 (thyroxine) and T3 (triiodothyronine) are the two main thyroid hormones. T4-only medications, such as Synthroid or generic levothyroxine, are the most commonly prescribed thyroid medications. That said, there are different thyroid hormone medications out there, including T3-only and T4/T3 combination options — the type and dosages should be individualized for each person.

For more information, you can download my free eBook, Optimizing Thyroid Medications, to help you get started on finding the right thyroid medication plan for you.

2. You May Need to Try a T3-Containing Medication

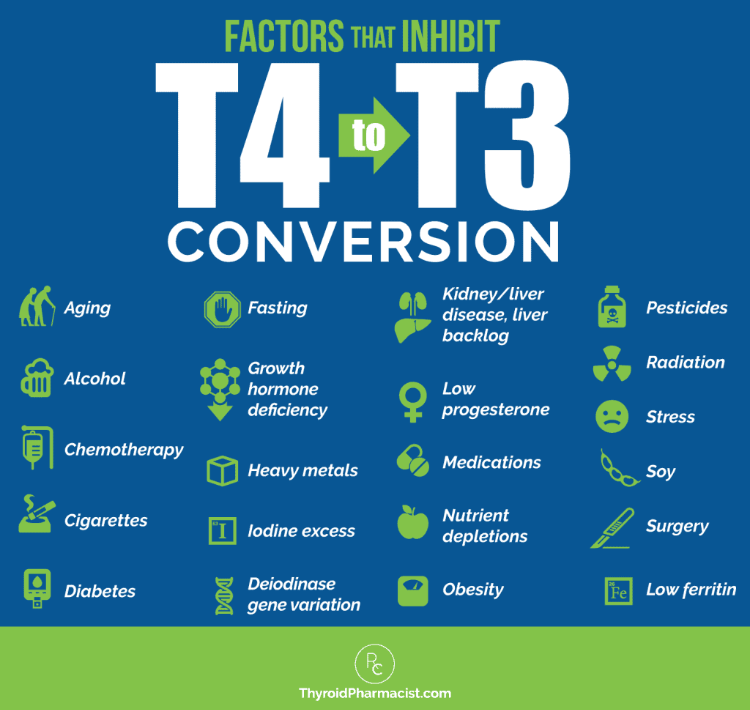

As mentioned above, T4 and T3 are the two main thyroid hormones, and T4-only medications are the most commonly prescribed thyroid medications.

While they are generally well tolerated, not every individual with Hashimoto’s is able to convert the T4 from their medication into T3 (the more biologically active thyroid hormone) due to factors such as aging, nutritional deficiencies, liver backlog, and more. As such, taking a T4-only-containing medication may not relieve all of one’s symptoms.

There may be an advantage to taking a T3-containing medication in such cases, and many individuals report feeling better on T4/T3 combination medications.

T3-only medications (such liothyronine, Cytomel, and compounded T3 medications) are typically used as an add-on to T4-only medications.

T4/T3 combination medications (like WP Thyroid, Nature-Throid, Armour Thyroid and compounded combo medications) are another option to consider. These types of medications mimic the ratio of thyroid hormones, T4 and T3, within our body.

You can check out my article reviewing thyroid medications to learn more about the pros and cons of each type of thyroid medication available on the market.

Remember, thyroid medications should be individualized, as different individuals will feel best on different types of medications, so be sure to consult a practitioner to find what may work best for you. (It’s important to note, however, that conventional doctors are not always comfortable with prescribing combination medications due to issues of poor-quality control and medication recalls, so you may wish to work with a functional medicine practitioner.)

3. Try Going Gluten Free

Gluten (a hard-to-digest protein found in foods made of wheat, barley or rye) can be a trigger for many individuals, and is the most common food sensitivity found in those with Hashimoto’s.

Gluten can create intestinal permeability, or leaky gut (one of the three factors required for autoimmunity to occur). Intestinal permeability occurs when there are “gaps” within the tight junctions of the intestinal barrier, allowing for digested food molecules, such as gluten, to leak out.

Once gluten “leaks out” and enters the bloodstream, it can lead the body to attack its own thyroid (as the body can confuse the structure of gluten with cellular components found in the thyroid gland), leading to gluten sensitivity.

For some individuals, gluten may be the sole trigger of their autoimmune thyroid disease. Thus, in some cases, we see a complete remission of the condition when an individual goes on a gluten-free diet. In other cases (88 percent of the time), the person feels significantly better and experiences a reduction in symptoms such as bloating, diarrhea, low energy, excess weight, constipation, stomach pain, acid reflux, hair loss, and anxiety.

4. Diet Can Have a Big Impact on Thyroid Health

As mentioned above, a gluten-free diet can be immensely helpful for those with Hashimoto’s whether gluten is the sole trigger of an individual’s Hashimoto’s, or there are other root causes involved. Making further dietary interventions can also be helpful in eliminating one’s thyroid symptoms and reducing thyroid antibodies. Some people have even been able to eliminate their thyroid antibodies through dietary changes alone!

It’s been my experience, and the experience of many of my clients, that along with gluten, eliminating dairy and soy can reduce inflammation and improve Hashimoto’s. In my survey of over 2000 individuals with Hashimoto’s, 57 percent said that they react to dairy, and around 80 percent said they felt better on a dairy-free diet. Similarly, 63 percent of individuals felt better on a soy-free diet.

As such, along with a gluten, dairy, and soy-free diet, other healing diets such as the Paleo or Autoimmune Paleo (AIP) diets, can be immensely beneficial as well, as they eliminate these common foods, help to reduce inflammation, and focus on nutrient-dense foods (helping to prevent nutrient deficiencies). Of the 2000+ individuals in my survey, 75 percent said that they felt better on an AIP diet.

That said, diets are not one-size-fits-all. While there isn’t one diet that works for everyone, I do recommend incorporating foods such as beets and cruciferous vegetables (some do better with cooked vegetables), pasture-raised meats, and probiotic-rich foods (such as kefir). And, as always, be sure to tailor any healing diet to your own needs!

To learn what a thyroid-healing diet entails, I recommend checking out my article on the best diet for Hashimoto’s.

5. You May Have a Selenium Deficiency

A selenium deficiency has been recognized as a nutrition-related trigger of Hashimoto’s.

Selenium is a nutrient that is needed for thyroid function. It’s crucial in our body’s conversion of the inactive thyroid hormone, T4, to the more biologically active thyroid hormone, T3. It also helps balance iodine levels (too much iodine can be harmful to the thyroid — more on that in a minute).

Selenium deficiency is associated with symptoms such as anxiety, low mood, depression, and fatigue, to name a few.

This deficiency is one of the most common nutrient deficiencies that I’ve seen in Hashimoto’s. One of the most common reasons why I see individuals become deficient in this nutrient is because they are on a gluten-free diet. While a gluten-free diet can be incredibly beneficial for the thyroid, it can be lacking in selenium, making an individual on this diet more susceptible to selenium deficiency.

A daily dose of 200 mcg of the selenomethionine form of selenium, has been shown to reduce thyroid antibodies by about 50 percent over the course of three months, in people with Hashimoto’s. Additionally, research has found that selenium supplementation, alongside myo-inositol supplementation, can help the thyroid revert to normal functioning (referred to as an euthyroid state).

In my experience, selenium can help people feel calmer, as well as improve energy levels and promote hair regrowth.

In my survey of over 2000 individuals with Hashimoto’s, 62 percent shared that selenium supplementation (at a dose of 200 mcg/day) helped them feel better. As this dose may be difficult to achieve through diet alone (one would have to consume large amounts of selenium-rich foods to obtain the recommended amount), I recommend a high-quality selenium supplement such as Selenium (Selenomethionine) by Pure Encapsulations.

6. Hashimoto’s and Iodine Deficiency-Induced Hypothyroidism Should Be Treated Differently

There is a lot of controversy surrounding iodine in the thyroid world. This nutrient, which is combined with the amino acid tyrosine to make thyroid hormones T3 and T4, is sometimes recommended as the one nutrient that all people with thyroid issues need more of. This is because iodine deficiency can lead to hypothyroidism.

However, medical professionals refer to iodine as a “Goldilocks” nutrient, as the levels have to be just right — low levels of this nutrient are needed for thyroid function, but high levels can be detrimental to thyroid health. In the case of Hashimoto’s, hypothyroidism induced by an iodine deficiency, is rare.

I have found that most people with thyroid disease have excess levels of iodine. Iodine excess may aggravate Hashimoto’s in some cases, leading to anxiety, irritability, brain fog, palpitations, and fatigue, as well as accelerated damage to the thyroid gland.

Iodine needs to be processed by the thyroid gland, and when the thyroid is inflamed, the processing of iodine will likely produce more inflammation. If you give an angry and overwhelmed organ more work to do, you’ll likely see it become even angrier!

A person may feel more energetic when first starting an iodine supplement, but lab tests will reveal that their “new energy” is coming from the destruction of thyroid tissue, which dumps thyroid hormone into the circulation. Reports will show an elevated TSH, elevated thyroid antibodies, and in some cases, low levels of active thyroid hormones.

This is why I don’t generally recommend iodine supplements to people with Hashimoto’s. I don’t believe that the short-term artificial boost in energy is worth destroying your thyroid gland!

In one study, researchers from the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota tracked the rate of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in patients from 1935 to 1967. Within two years, the doctors saw an increase in autoimmune thyroid disease caused by iodine fortification in table salt and processed food.

That said, the low doses of iodine (150 mcg–220 mcg) that are found in multivitamins and prenatal vitamins, are generally safe for people with Hashimoto’s. To learn more about dosing iodine for those with Hashimoto’s, check out my article on iodine here.

7. Your Hair Loss Could Be Caused by Low Ferritin

Hair loss is a common symptom in those with Hashimoto’s. Along with selenium, ferritin — a stored form of iron (and an accurate predictor of iron stores) — is a nutrient that is often depleted in Hashimoto’s.

This nutrient is required for the utilization of the thyroid hormone T3 by cells. Thus, if low ferritin leads to an individual not being able to utilize T3 well, the thyroid may slow down its metabolism and conserve resources for more important physiological processes. As hair isn’t high on this priority list, ferritin depletion will then lead to hair loss.

I highly recommend checking ferritin levels for any woman who is experiencing hair loss and/or has Hashimoto’s. Normal ferritin levels for women are between 20 and 200 ng/mL. However, the optimal ferritin level for thyroid function is between 90-110 ng/mL — this is the range that is most conducive to healthy, lustrous hair (and overall well-being).

Most men are not lacking in ferritin (compared to women who are at higher risk of low ferritin due to menstruation).

Regardless of gender, you can check your ferritin levels easily with Ulta Lab Tests.

If you are found to be low in ferritin, I recommend supplementing with OptiFerin-C by Pure Encapsulations at a dose of 1-3 capsules per day, in divided doses, taken with meals.

8. You Are Not Going Crazy!

When patients come in describing mood imbalances or reporting that they feel “crazy,” doctors are often quick to suggest a mood disorder (and often, antidepressants) without investigating thyroid health. If this sounds like something you’ve experienced, please know that the anxiety, depression, irritability, mood swings, and emotional numbness you are feeling, could be related to your thyroid.

Specifically, an increase in thyroid antibodies can contribute to these mood imbalances.

Thyroid antibodies are a marker of autoimmune thyroid disease. They let us know that the immune system is destroying thyroid tissue, which can cause a release of hormones into the bloodstream. This can lead to transient (or temporary) hyperthyroidism, as well as mood-related symptoms such as anxiety and irritability. The transient hyperthyroidism is soon followed by an onset of hypothyroidism, resulting in apathy and depression.

Another reason for low mood and/or anxiety may be due to blood sugar imbalances.

Taking the right thyroid medication for you, considering selenium supplementation if needed (as mentioned earlier in this article), and balancing blood sugar (dips in blood sugar can lead to low mood), can all help with mood regulation. In fact, I recommend focusing on these strategies before considering antidepressants.

For an in-depth explanation of the root cause approach to improving low mood, I recommend reading my articles on anxiety and depression.

9. It’s Important to Monitor Your TPO and TG Antibody Levels

There are two types of thyroid antibodies associated with Hashimoto’s: thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO antibodies) and thyroglobulin antibodies (TG antibodies). These are markers of how aggressive the attack is on your thyroid gland, and can be used as a marker to track the progress of your condition (and healing!).

These antibodies can show up as elevated long before other, more commonly tested markers of thyroid health — TSH (optimal range is between 0.5-2 μIU/mL), free T3 (optimal range is 5-7 pmol/L), and free T4 (optimal range is 15-23 pmol/L) — appear as out of range (sometimes as early as 5 to 15 years before a diagnosis is made).

They are often elevated in subclinical hypothyroidism, which is an earlier stage of Hashimoto’s, and are warning signs of thyroid disease (even if TSH comes back “normal” on a lab test). About 80 to 90 percent of people with Hashimoto’s will have either elevated TPO or TG antibodies, or both.

The normal values for TPO and TG antibodies are <35 IU/mL. However, according to the Institute of Functional Medicine, the optimal ranges (where most individuals feel best) are <2 IU/mL for both types of antibodies.

When I underwent a physical exam in 2009, my lab results showed my thyroid antibodies to be at over 2000 IU/mL. After hours of researching and much trial and error, I found some research suggesting methods such as following a gluten-free diet and supplementing with selenium, could reduce antibodies by 20 to 50 percent (I personally found these two methods to help decrease my antibodies).

Antibodies fluctuate in response to triggers and lifestyle habits. As you make changes to your lifestyle and diet (and medications as discussed with your doctor), you should retest your antibodies every three months to see if your lifestyle and/or diet interventions are working.

You can learn more about thyroid antibodies here.

10. Your Thyroid May Function and Work on Its Own Again in the Future

Most conventional doctors will say that Hashimoto’s, and other thyroid diseases, are irreversible and require one to stay on thyroid medication for the rest of their life.

It is true that some individuals may find that along with addressing their root causes, they function best with thyroid medications, and may opt to use medications long-term to live their best life. However, it is also possible to recover thyroid function.

Research shows that once the autoimmune attack on the thyroid stops, the thyroid gland has the ability to recover function. It has also been shown that thyroid function spontaneously recovers in 20 percent of Hashimoto’s patients (referred to as a euthyroid state).

One case study examined the occurrence of three girls who spontaneously recovered (either partially or fully) from autoimmune hypothyroidism (before starting medications). None of them had excessive levels of iodine or goitrogens during the study investigation. The authors suggested that their recovery may have been due to their elimination of iodine (which can aggravate hypothyroidism and Hashimoto’s), and/or not taking suboptimal medication(s) that may have made them feel worse.

So what does this mean? Addressing the root causes behind the autoimmune attack on the thyroid, can reverse the autoimmunity!

Going gluten free, incorporating selenium, and targeting the root cause(s) behind the development of Hashimoto’s, are some ways to reduce or stop the autoimmune attack on the thyroid. Innovative new therapies like low level laser therapy may also help people improve the function of their thyroid and wean off meds. You can read more about addressing the most common root causes of Hashimoto’s here.

If, at some point in your journey, you are interested in seeing whether you may be able to wean off thyroid medications, there is a test that you can do — the test involves thyrotropin-releasing hormone (or TRH) to be administered by a doctor (this article goes into detail on the full procedure).

The Takeaway

Hashimoto’s is a complex and challenging condition to navigate. Sometimes, despite their best intentions, not every endocrinologist will have a grasp on the set of unique characteristics and root cause factors associated with Hashimoto’s. I wasn’t told many of these things, and had to learn through trial and error.

Sometimes, we need to be Root Cause Rebels and advocate for our own health. That could mean learning the effects of gluten on the thyroid, identifying nutrient deficiencies commonly observed in Hashimoto’s, or looking into the variety of options available for thyroid medications — all of these are immensely helpful in digging deeper into our root cause(s) and addressing them.

There are so many other things that can be helpful as well! The mission behind my first book, Hashimoto’s: The Root Cause, was to spread awareness about lifestyle interventions for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Personally, they have made a huge difference in my life, and after addressing all of my root causes, I was able to put my thyroid condition into remission! (Read about my success story here.)

My book Hashimoto’s Protocol builds on this information to deliver guided protocols for finding and addressing your own root causes.

I want to empower patients with knowledge — and also hope — that every person who is diagnosed with Hashimoto’s, will be able to walk into his/her physician’s office to learn about lifestyle interventions that will help them feel like themselves again. We may even get to the point of being able to reverse autoimmunity.

I wish you all the best in your healing journey!

References

Katarzyna K, Jarosz C, Agnieszka S et al. L-thyroxine Stabilizes Autoimmune Inflammatory Process in Euthyroid Nongoitrous Children with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis and Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of Clinical Research in Pediatric Endocrinology. 2013;5(4):240-244. doi:10.4274/jcrpe.1136.

Span P. Could Be the Thyroid; Could Be Ennui. Either Way, the Drug Isn’t Helping. Nytimescom. 2017. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/21/health/could-be-the-thyroid-could-be-ennui-either-way-the-drug-isnt-helping.html. Accessed August 8, 2017.

Stott D, Rodondi N, Kearney P et al. Thyroid Hormone Therapy for Older Adults with Subclinical Hypothyroidism. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376(26):2534-2544. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1603825.

Wiersinga W. Paradigm shifts in thyroid hormone replacement therapies for hypothyroidism. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2014;10(3):164-174. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2013.258.

Taylor PN, Eligar V, Muller I, Scholz A, Dayan C, Okosieme O. Combination Thyroid Hormone Replacement; Knowns and Unknowns. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:706.

Dayan C, Panicker V. Management of hypothyroidism with combination thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) hormone replacement in clinical practice: a review of suggested guidance. Thyroid Res. 2018;11:1.

Sategna-Guidetti C, Volta U, Ciacci C et al. Prevalence of thyroid disorders in untreated adult celiac disease patients and effect of gluten withdrawal: an Italian multicenter study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001;96(3):751-757. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03617.x.

Lerner A, Jeremias P, Matthias T. Gut-thyroid axis and celiac disease. Endocrine Connections. 2017;6(4):R52-R58. doi:10.1530/EC-17-0021.

Vojdani A, Tarash I. Cross-Reaction between Gliadin and Different Food and Tissue Antigens. Food and Nutrition Sciences. 2013;4(1):20-32. doi:10.4236/fns.2013.41005.

Virili C et al. Atypical celiac disease as cause of increased need for thyroxine: a systematic study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97(3):E419-E422. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-1851.

Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(3):286-292.

Ventura M, Melo M, Carrilho F. Selenium and Thyroid Disease: From Pathophysiology to Treatment. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2017;2017:1297658. doi:10.1155/2017/1297658.

Gärtner R, Gasnier BC, Dietrich JW, Krebs B, Angstwurm MW. Selenium supplementation in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis decreases thyroid peroxidase antibodies concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(4):1687-1691.

Gärtner R, Gasnier BC. Selenium in the treatment of autoimmune thyroiditis. Biofactors. 2003;19:165–70.

Contempre B, Dumont J, Ngo B, et al. Effect of selenium supplementation in hypothyroid subjects of an iodine and selenium deficient area: the possible danger of indiscriminate supplementation of iodine-deficient subjects with selenium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;73(1):213-215. doi:10.1210/jcem-73-1-213.

Rink T, Schroth H, Holle L, Garth H. Effect of iodine and thyroid hormones in the induction and therapy of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Nuklearmedizin. 2016;1999(38(5):144-9.

Zhao H, Tian Y, Liu Z, et al. Correlation between iodine intake and thyroid disorders: a cross-sectional study from the south of China. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;162(1-3):87-94. doi:10.1007/s12011-014-0102-9.

Xu J, Liu X, Yang X, et al. Supplemental selenium alleviates the toxic effects of excessive iodine on thyroid. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2011 Jun;141(1-3):110-8. doi: 10.1007/s12011-010-8728-8.

Phillips T, Slomiany W, Allison R. Hair loss: Common causes and treatment. DO Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(6):371378.

Eftekhari MH, Keshavarz SA, Jalali M, Elguero E, Eshraghian MR, Simondon KB. The relationship between iron status and thyroid hormone concentration in iron-deficient adolescent Iranian girls. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition. 2006; 15(1), 50.

Carta M, Loviselli A, Hardoy M et al. The link between thyroid autoimmunity (antithyroid peroxidase autoantibodies) with anxiety and mood disorders in the community: a field of interest for public health in the future. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4(1). doi:10.1186/1471-244x-4-25.

Cooper R, Lerer B. The use of thyroid hormones in the treatment of depression. Harefuah. 2010:529-34, 550, 549.

Barbesino G. Drugs Affecting Thyroid Function. Thyroid. 2010;20(7):763-770. doi:10.1089/thy.2010.1635.

Gaynes B, Rush A, Trivedi M, Wisniewski S, Spencer D, Fava M. The STAR*D study: treating depression in the real world. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2008;75(1):57-66. doi:10.3949/ccjm.75.1.57.

Wentz I. Top 9 takeaways from 2232 people with Hashimoto’s. Thyroid Pharmacist. https://thyroidpharmacist.com/articles/top-9-takeaways-from-2232-people-with-hashimotos/. Published June 22, 2015. Accessed June 26, 2015.

Lee, Hae Sang HS. The natural course of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in children and adolescents. Journal of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism. 2014;27(9-10):807.

Höfling DB Low-level laser in the treatment of patients with hypothyroidism induced by chronic autoimmune thyroiditis: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2013;28(3):743-53.doi: 10.1007/s10103-012-1129-9.

Carta M, Loviselli A, Hardoy M et al. The link between thyroid autoimmunity (antithyroid peroxidase autoantibodies) with anxiety and mood disorders in the community: a field of interest for public health in the future. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4(1). doi:10.1186/1471-244x-4-25.

Kaplowitz, PB. Case report: rapid spontaneous recovery from severe hypothyroidism in 2 teenage girls. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2012;9(2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-9856-2012-9

Rink T, Schroth H, Holle L, Garth H. Effect of iodine and thyroid hormones in the induction and therapy of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Nuklearmedizin. 2016;1999(38(5):144-9.

Note: Originally published in February 2015, this article has been revised and updated for accuracy and thoroughness.